The Language of Attachment

From the 1970’s to today, famed relationship researcher Dr John Gottman, in conjunction with various colleagues, has spent thousands of hours observing relationship interactions in an attempt to decode the patterns that foster or erode relationship stability and contentment. He has identified that relationships, in essence, are made up of a series of “bids” for connection.

A bid is any attempt by one person to establish a positive moment of connection with another. This can be something as simple as a smile or a gentle touch, or it can show up in more complex ways, such as a request for help, or an invitation to participate in a joint activity or moment of shared interest. In healthy relationships, a person’s bids for connection will usually be met with active interest and engagement. In Gottman language, this is known as a “turn-towards” response. Conversely, “turn-away” responses occur when bid requests are missed, ignored, or minimally engaged with. Turn-away responses aren’t necessarily a deliberate attempt to be dismissive. For example, they may just reflect a person being preoccupied with something else. Nevertheless, a high proportion of turn-away responses is one of the most reliable indicators of relationship dysfunction.

Bid responses are so vital to the health of a relationship that Gottman can famously predict with 94% accuracy whether a marriage will end in divorce just by tracking the interplay of turn-towards and turn-away responses between a couple over the course of a five-minute interaction. But this doesn’t tell the whole story. It’s not just the mechanics of these responses that determine their impact on a relationship - it’s what they represent.

This is where attachment theory can shed some light.

Attachment theory is best known in reference to studies that demonstrated the fundamental need for young children to feel safe and secure in their bonds with parents and caregivers. It turns out that the same needs and longings for safety and security exist in older children and adults. In fact, it is the thwarting of these needs that is at the heart of the vast majority of relationship distress.

Our attachment-related concerns can be summarised in two questions, each reflecting a different attachment insecurity:

1) Will you be there for me if I need you?

2) Am I enough for you?

The first question relates to safety and trust. It’s a check-in to test another person’s availability, responsiveness, and willingness to be close. “If I need support, understanding or affirmation, will you be attuned to my needs and able to respond to them? Can I trust you to be present for me?” These reassurances are an important component of establishing a sense of being safe and protected within the world.

The second question relates to worth, acceptance and lovability. “Do I matter to you? Do I offer value to your life? Am I wanted here? Do you respect me?” We all rely upon our attachment figures to reassure us of these things. The second question may read with a blank. “Am I ________ enough for you?” This can be filled by whatever insecurity (or insecurities) are relevant to a particular person in a particular relationship. “Am I good enough / attractive enough / interesting / intelligent / rich / successful / fun / attentive / scholarly / sporty enough for you?” To a greater or lesser extent, everyone has an adjective that fits in the blank.

Returning to Gottman’s bids, we can see that each bid is not just a surface level request for attention. Embedded in our bids is one, or both, of these attachment questions. When a child asks her parents for help with a homework assignment, she is also looking for reassurance that they are there for her and responsive to her needs. That she is safe and supported. When we smile warmly at our partner and they smile back, we are reassured of our worth and value to them. Turn-towards responses foster healthy relationships, because they help meet our attachment needs of feeling safe and valued. Every turn-towards response is a little building block of attachment security.

But there’s something interesting that happens when bids for connection are routinely met with a turn-away response. Instead of providing the reassurance that people are seeking about their safety and worth, regular turn-away responses activate an escalation of attachment anxieties. And as with any anxiety, there are predictable patterns of behaviour that result. In particular, you will see avoidance behaviour.

In my practice, I’ve observed that in most relationships avoidance behaviour tends to manifest differently according to whether a person’s attachment anxieties relate primarily to their sense of safety (question 1) or worth (question 2) in the relationship. For this reason, in dysfunctional relationship dynamics you can take a pretty good guess as to what a person is feeling insecure about based upon their behaviour. Let’s look at them each in turn…

Safety: A person whose need to feel safe within a relationship is not being met tends to move towards the other person, in an attempt to avoid the feeling of distance with them. When anxieties are activated, this can often take the form of critical pursuit - finding fault, or expressing disapproval. In more extreme cases, critical pursuit may cross the line into controlling behaviours. In romantic relationships, critical pursuit often emerges when the pursuer perceives their partner to be in some way unavailable to them, or a source of attachment danger. In family relationships, parents often fall into the critical pursuer role when they are feeling anxious about their child’s unresponsiveness to their concerns or expectations. The pursuer will commonly relate to statements such as “You’re not there for me”, “You don’t make me a priority”, or “I can’t trust you”.

Worth: On the other hand, a person whose sense of worth is being undermined within a relationship dynamic tends to seek distance from the other person, to avoid conflict, or avoid further interactions which cause them to feel devalued, inadequate, or not accepted. When they feel cornered by the pursuer, the distancer will often then become defensive, and this is when things may erupt into conflict. The distancer will commonly relate to statements such as “I can’t do anything right by you”, “You only see the worst in me”, “I’m just a disappointment to you”, or “You don’t believe in me.”

It is easy to see how these roles feed into each other, creating a cycle in which each person fuels the other’s attachment anxieties. The pursuer is critical, activating the distancer’s anxiety that they are not valued. The distancer then withdraws, further inflaming the pursuer’s anxiety that the other person is not available to them… and so on. This is a well-known and common pattern seen in relationships, called the pursuer-distancer cycle. Each person’s behaviour in this cycle can be understood as a coping strategy, or form of protest against the other’s failure to meet their attachment needs.

Once we learn to translate others’ bids for shared connection, and their protest behaviours when the bids are not met, into the language of attachment, we are able to respond in a way that better affirms people’s sense of safety and value within our relationships.

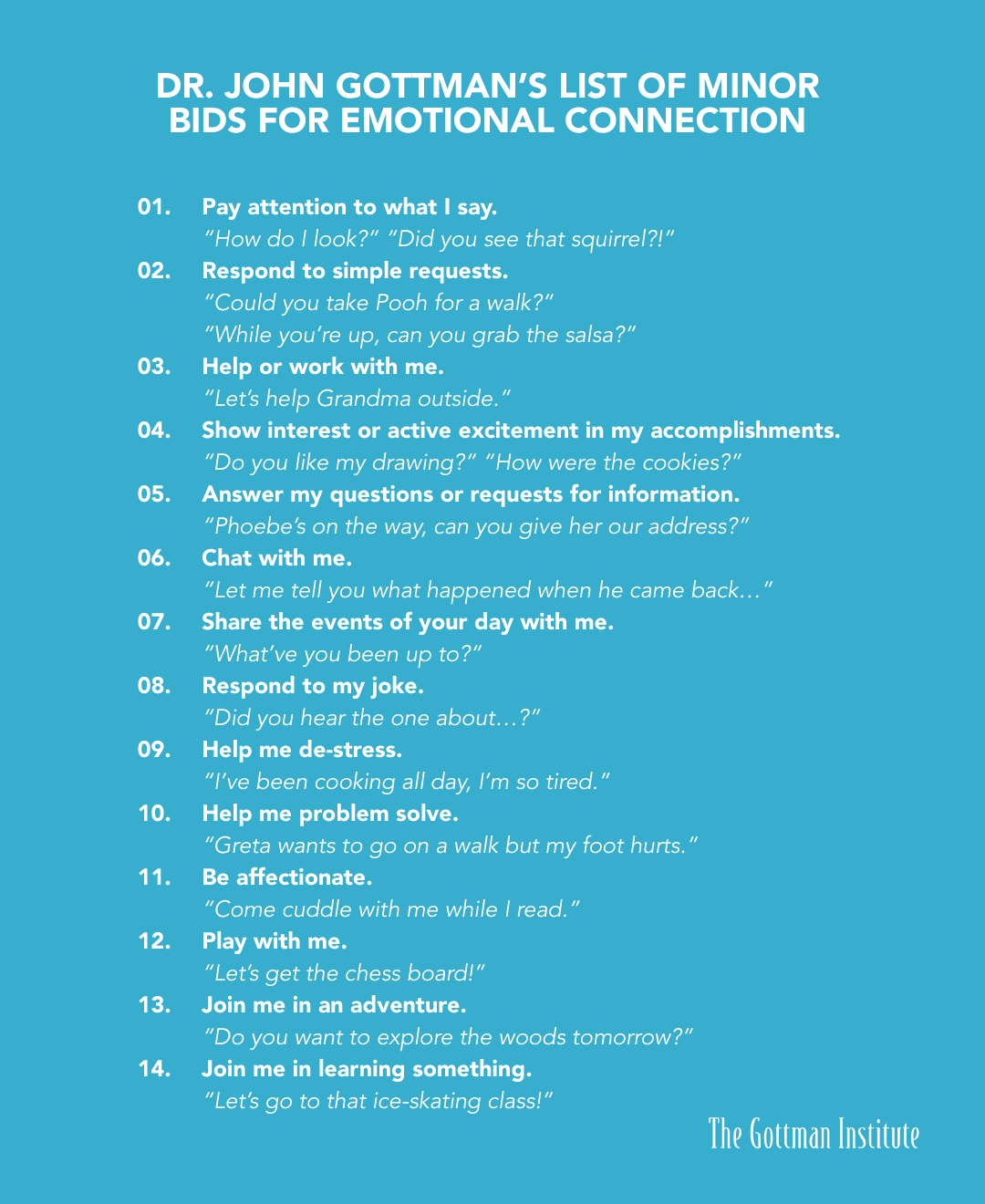

For an idea about how you might apply this understanding in your own relationships, have a look below at a list, created by Dr John Gottman, of typical, everyday bids people might make, and see if you can identify the possible attachment needs that might lie beneath. Can we reframe each of the below bids into a check-in for reassurance relating to one, or both, of the questions underlying our attachment needs?

Here’s a little primer of our attachment questions for you to bear in mind as you read through.

1) Will you be there for me if I need you? (Checking in on the other’s responsiveness, availability and attunement to our needs in order to promote feelings of being safe and supported within the relationship and the world.)

2) Am I enough for you? (Checking in with the other for reassurances of their interest in and respect for us and our experiences, in order to promote feelings of worth, value and acceptance.)